Design Research Methods & Contexts

Background Research—Observational Data

During the first week of the research, I conducted field visits to multiple op shops, second-hand stores, and shopping centers in the Auckland region, including Mount Albert, St Lukes Mall, Ponsonby, Summer Street, and K Road. These visits provided an opportunity to observe consumer interactions with second-hand and recycled clothing, as well as their shopping behaviors. The initial visit to the Mount Albert op shop offered valuable insights into the operations of donation-based charity retail, including the processes of sorting, aggregation, and the management of unsalable garments by volunteers and staff. I also checked the garments displayed for sale and recorded detailed information on their material composition by capturing photos and notes. In addition, semi-structured interviews were conducted with volunteer staff and the shop manager to gain a deeper understanding of operational practices and consumer engagement. Additionally, I consulted Veronica, an alumna of Media Design School and currently a fashion design lecturer, to gain insights into the challenges of fast fashion and to understand how fashion design students and activists engage in sustainable practices.

My second field visit was to Ponsomby and K Road, areas known for a housing mix of recycled and branded clothing stores. I visited a range of shops and observed their practices and the customers, noting that, as it was a Monday, many staff members were busy with restocking the stocks, and fewer customer visits were noticed. Tatt y’s Designer Recycle store, for example, displayed a selection of pre-loved designer garments. However, when I checked the price tags, I observed that many of the garments’ costs were relatively high despite being secondhand. Moral Fiber, Search & Destroy, and the Ponsomby SPCA shop had relatively expensive clothing as well. Moreover, the garments carried high-fashion brand tags, but most of the items appear ordinary in design. Many of those dresses are similar to standard dresses available at a much lower cost in my home country. These observations underscored the value placed on designer clothes within the second-hand retail market, pointing to the limited accessibility and affordability of fashion options for youth. From the perspective of my research, this highlights the potential of upcycling and DIY refashioning as strategies to make sustainable fashion both accessible and appealing to younger generations.

During these visits, I observed that most customers were women from different age groups. I approached a few customers and had informal conversations to understand their motivations for shopping second-hand. Several customers mentioned that brand-new clothing has become increasingly expensive, and second-hand clothing as an alternative is affordable and budget-friendly for them. I interviewed a staff member of the Ruby shop, who explained the shop actively promotes sustainable practices, as they operate a take-back scheme where customers can drop their used clothes in exchange for a gift voucher, which is redeemable for new clothes. This initiative is significant, as some of the retailers are trying to integrate circular economy principles into their business models. Additionally, the shop had fabric scraps that anyone could pick, and a completed bag sample accompanied some guides on how to make a DIY bag from fabric scraps as inspiration. They even had pouches for sale, which are made out of fabric scraps.

These initiatives highlight a growing awareness among some retailers of the environmental and social impact caused by fast fashion. For my project, these insights reinforce the potential of workshops and upcycling prototypes as effective tools to encourage more conscious and creative approaches to fashion consumption.

Research Synthesis: Observational Insights and Hypothetical User Scenarios

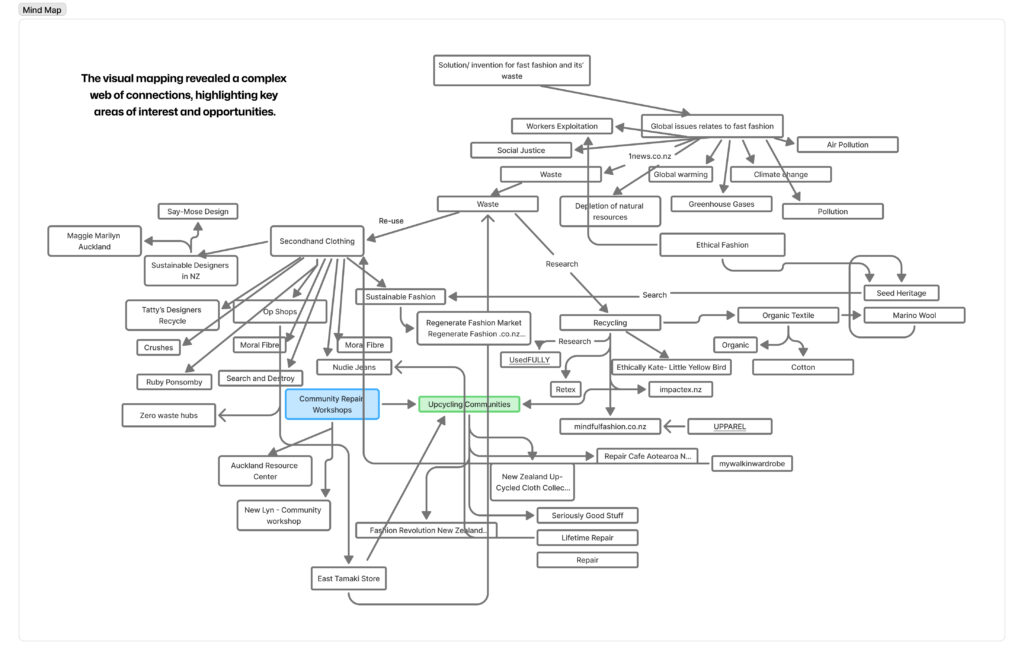

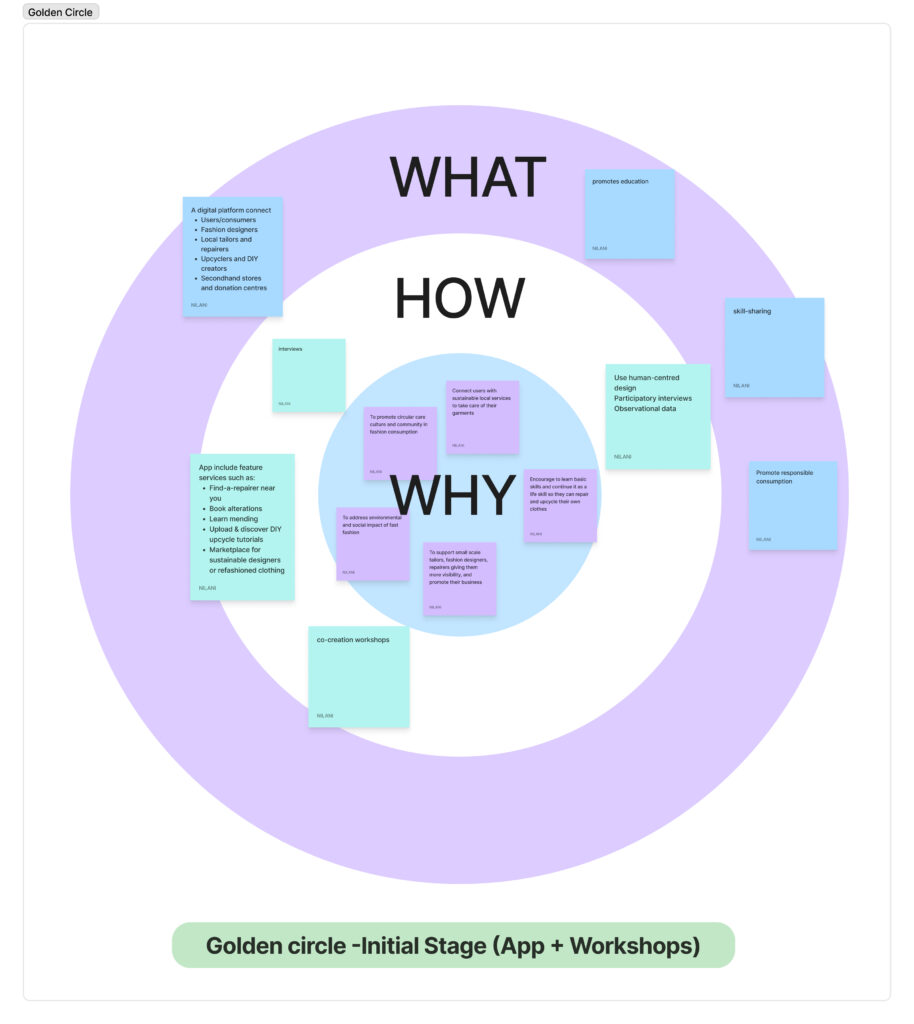

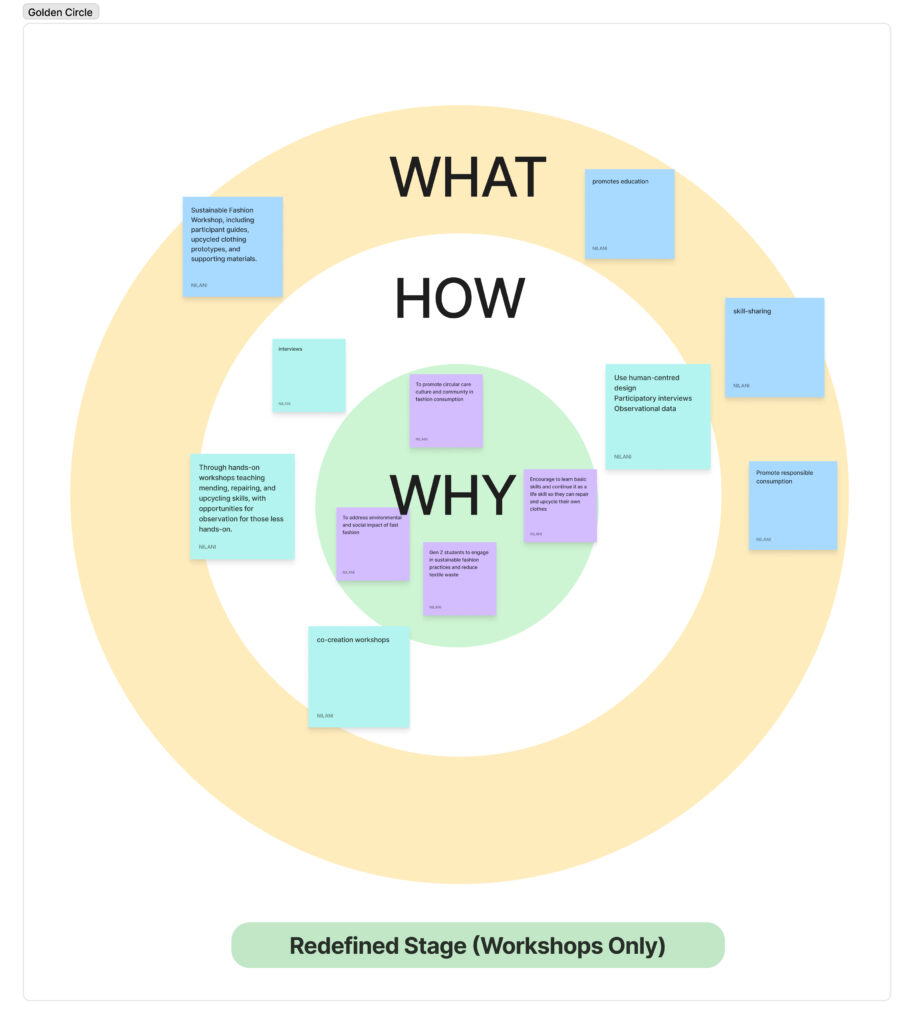

EVOLUTION OF PROJECT PURPOSE – THE GOLDEN CIRCLE

“People don’t buy what you do; they buy why you do it.” (Sinek, 2009)

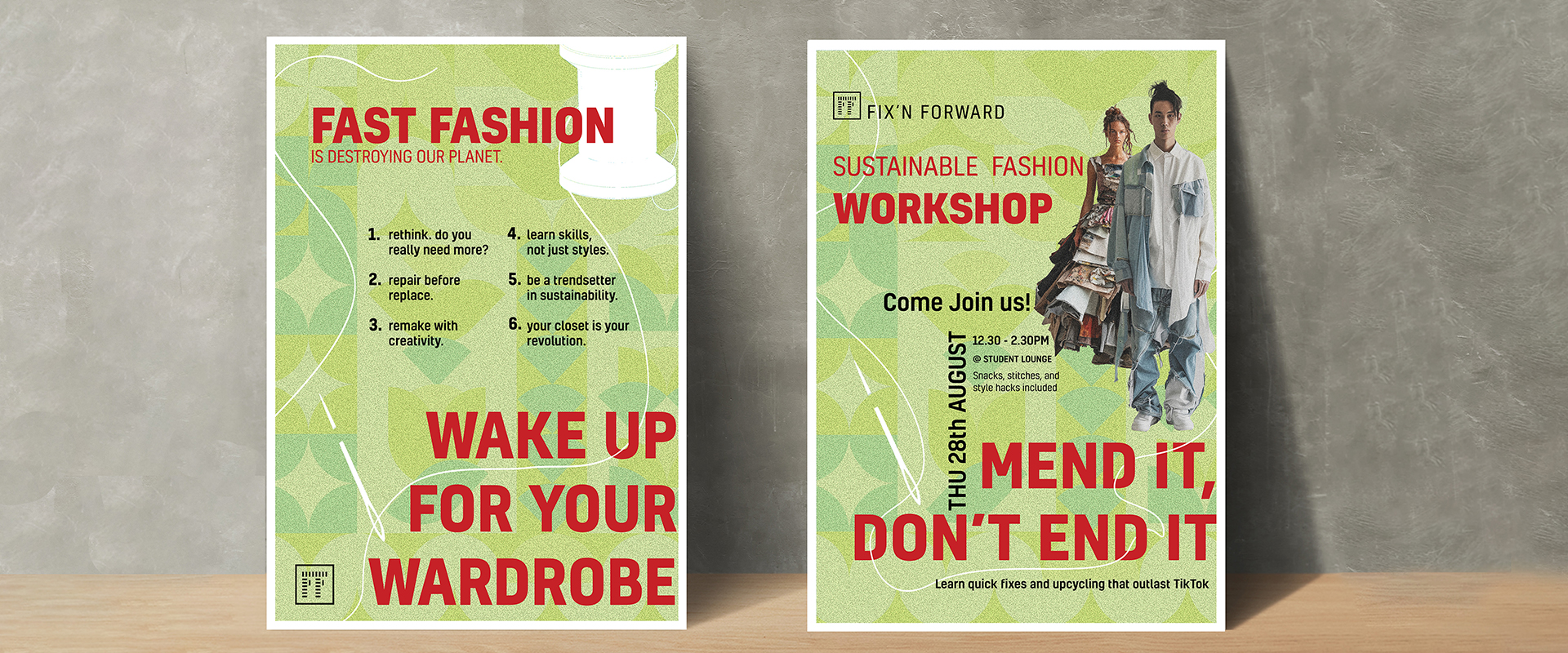

The Golden Circle framework (Sinek,2009) highlights that effective projects and organizations begin with a clear understanding of purpose (Why) before outlining the process (How) and the outcomes (What). The “Why” behind this project is to discuss the environmental and social impacts of fast fashion. The “How ” involves designing engaging workshops that inspire and educate Gen Z students about sustainable fashion practices.

The “What” is the delivery of hands- on sessions that focus on mending, upcycling, and conscious consumer choices.

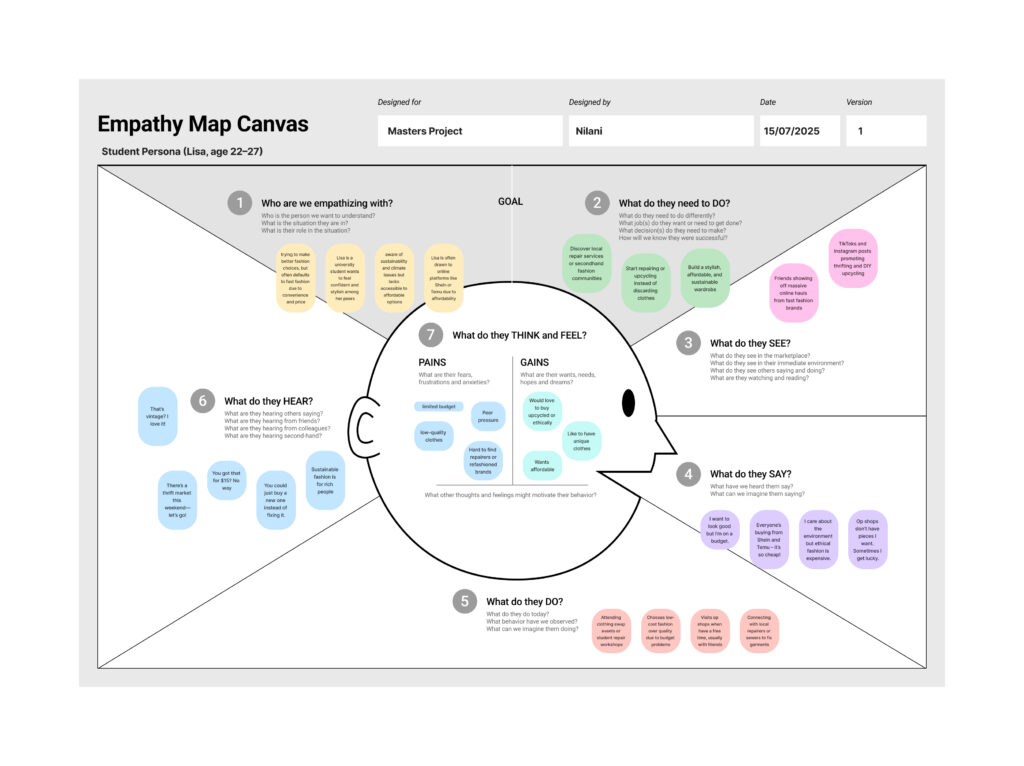

Empathy Map Canvas

User Journey Map

METHEDOLOGY

Qualitative and Practice-Based Research

The project used a mix of methodologies in a discovery-led process of open-ended inquiry, incorporating my own creative practice. Denzin and Giardina (2007) and Denzin and Lincoln (2011) provide useful guidance on research design and ethical considerations in qualitative research. Charmaz ’s (2002) grounded theory methodology was applied to support participant-led inquiry, gathering qualitative feedback from workshop participants on their experiences, needs, and engagement with repair and upcycling. I adopted a practice-based research methodology because of the project’s hands-on nature, which involved creating and testing upcycled clothing prototypes. Iterative exploration was made possible by this combination, which linked participant insights with useful prototyping to guide sustainable fashion practices.

Target Audience

Consumers concerned with environmental and ethical issues are increasingly moving toward alternative fashion practices such as upcycling and re-fashioning, which extend the life of garments and reduce landfill waste (Farrer & Fraser, 2009). Earlier concepts like the “User as Maker “ (Fletcher, 2008) highlighted a cultural shift where people take a more active role in customising and co-creating fashion. Today, this potential is even stronger with Generation Z, who are highly responsive to sustainability innovation. My project builds on this by targeting Gen Z through teaching and upskilling in basic stitching, repairing, and upcycling, encouraging these activities to become everyday habits.

Research Methods

A series of semi-structured interviews has been conducted with campus students to inform the research objectives to guide the development of the workshop plan and materials, and it enables an understanding of participants’ awareness of fast fashion and sustainable fashion and attitudes toward clothing reuse, repair, and upcycling. Therefore, I conducted one-on-one interviews with open-ended questions to encourage conversation and discussion.

Interview data organized into separate user profiles, illustrating individual behaviors, motivations, needs, and frustrations.

Note. Created by the author based on qualitative interviews with students.

RESEARCH SYNTHESIS

Research Synthesis Methods and Tools

After conducting qualitative interviews with students, I synthesized the findings through a range of human-centered design methods and tools, including affinity mapping, journey mapping, empathy mapping, persona development, and story mapping. The integration of these tools provided a comprehensive understanding of user behaviors, motivations, and pain points. This multi-method approach allowed me to identify key opportunity areas and helped plan and develop the proposed solution.

Affinity Mapping

The interview participants included Yonsoo, Maria 1, Maria 2, Anne, and Juno. Following the completion of the interviews, the collected data were organized and analyzed using an affinity mapping approach. This method allowed me to cluster interview insights into meaningful themes, including motivations, attitudes, frustrations, skills and actions, suggestions, and needs. The resulting themes provided a structured understanding of user perspectives, which informed the design of the workshop content, materials, and activities.

“Affinity mapping is a qualitative analysis technique used to synthesize large volumes of data by clustering individual observations or insights into meaningful themes. This method supports the identification of shared patterns and recurring issues, allowing researchers to move from raw data to actionable insights.”

(Hanington & Martin, 2012; Beyer & Holtzblatt, 1999)

Analysis of the interview data revealed two distinct student groups. The first group showed active interest in sustainable fashion practices, such as mending, repairing, and upcycling, and was motivated to engage hands-on. The second group valued sustainability but thought stitching, repairing, and upcycling were time-consuming, making them less likely to participate directly; however, they expressed interest in observing and learning from the workshop activities. Based on these findings, I developed two personas representing these two student groups. These personas informed the creation of journey maps and story maps, providing a framework for designing workshop experiences that cater to both hands-on participants and observational learners.

Key Insights from Student Interviews

Group A : Motivated but lack skills

(Value sustainability but perceive stitching, repairing, and upcycling as time-consuming)

- Support sustainable fashion in principle but unlikely to engage in hands- on repair / upcycling.

- Interested in observing workshops to gain knowledge and inspiration.

- Prefer accessible and low- e ff or t ways to contribute, such as donating or buying ethically.

- Appreciate seeing techniques demonstrated rather than per forming them themselves.

- May be motivated by visual examples, storytelling, or demonstrations.

- C oncerned with time constraints and convenience when considering DIY practices.

- Awareness of fast fashion impacts exists but doesn ’ t always translate into active par ticipation.

Group B : Motivated and has skills

(Interested in sustainable fashion and actively engaging in mending, repairing, and upcycling)

- Motivated to repair, mend, and upcycle clothing themselves.

- Value creativity and personalization in clothing.

- Actively seek ways to extend the life of garments.

- Interested in learning new skills like sewing, embroidery, and DIY projects.

- Respond positively to interactive workshops where they can practice hands- on techniques.

- Environmentally conscious and see their actions as contributing to sustainability.

- Enjoy collaborative learning and sharing experiences with peers.

Kansei Engineering

Kansei Engineering offers a valuable lens for understanding how people emotionally connect to everyday objects—an essential part of encouraging sustainable habits around clothing repair and reuse. Rather than focusing solely on function, the methodology looks at how sensory impressions—such as the feel of a mended seam or the visual texture of upcycled fabric—shape emotional meaning and personal attachment (Shütte et al., 2008). In Fix’n Forward, this approach helps explain why some garments become cherished and repaired, while others are easily discarded. By translating users’ emotional reactions into design insights, the project supports the creation of workshop experiences that strengthen emotional durability and deepen participants’ relationships with their clothing.

Because Kansei Engineering draws from lived experiences with existing products, it is well suited to a project centred on hands-on repair and material exploration. Participants’ sensory interactions—touching thread, selecting patches, feeling the weight of tools—become part of how they form new emotional associations with their garments. Understanding these affective responses helps inform workshop structures that prioritise care, agency, and connection, contributing to longer garment lifespans and more mindful consumption behaviours (Shütte et al., 2008).

Design Persona

Persona design was used in Fix’n Forward to create a grounded and empathetic understanding of the young participants engaging in repair culture. Rather than abstract user categories, personas allowed a clear picture of Gen Z learners—their motivations, frustrations, aesthetic preferences, and sustainability attitudes. Constructing a persona helped identify how tone of voice, workshop pacing, and visual communication could resonate with learners who value creativity, authenticity, and social impact. Mapping desirable and undesirable traits provided clarity on how the repair experience should feel: empowering, approachable, and fun, rather than intimidating or overly technical.

Moodboards and emotional cues further shaped how the workshop communicated with participants, from colour palettes and textures to the language used in instructions and prompts. Drawing on emotional design principles such as surprise, delight, and anticipation (Walter, 2001; Van Gorp & Adams, 2012), the persona helped guide the creation of a learning environment where repairing clothes feels expressive, rewarding, and socially meaningful. This approach strengthens the project’s intention to normalise repair as an everyday, sustainable practice and to engage young people in rethinking their relationship to fashion and consumption.

PERSONA DEVELOPMENT

REFERENCES

Charmaz, K. (2002). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

Denzin, N. K., & Giardina, M. D. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and the conservative challenge. Left Coast Press.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2011). The Sage handbook of qualitative research (4th ed.). Sage.

Fletcher, K. (2008). Sustainable fashion and textiles: Design journeys. Earthscan.

Hanington, B., & Martin, B. (2012). Universal methods of design: 100 ways to research complex problems, develop innovative ideas, and design effective solutions. Beverly, MA:Rockpor t.

Sinek, S. (2009). Start with why: How great leaders inspire everyone to take action. Portfolio.

Shütte, S., Eklund, J., Ishihara, S., & Nagamachi, M. (2008). Affective meaning: The Kansei engineering approach. In H. Schifferstein & P. Hekkert (Eds.), Product experience (pp. 477–496). Elsevier.

Van Gorp, T., & Adams, E. (2012). Design for emotion. Elsevier.

Walter, A. (2001). Designing for emotion. A Book Apart.

Leave a Reply