Human-Centred Experience Design

FIX’N FORWARD—A SUSTAINABLE FASHION WORKSHOP

PROJECT OVERVIEW

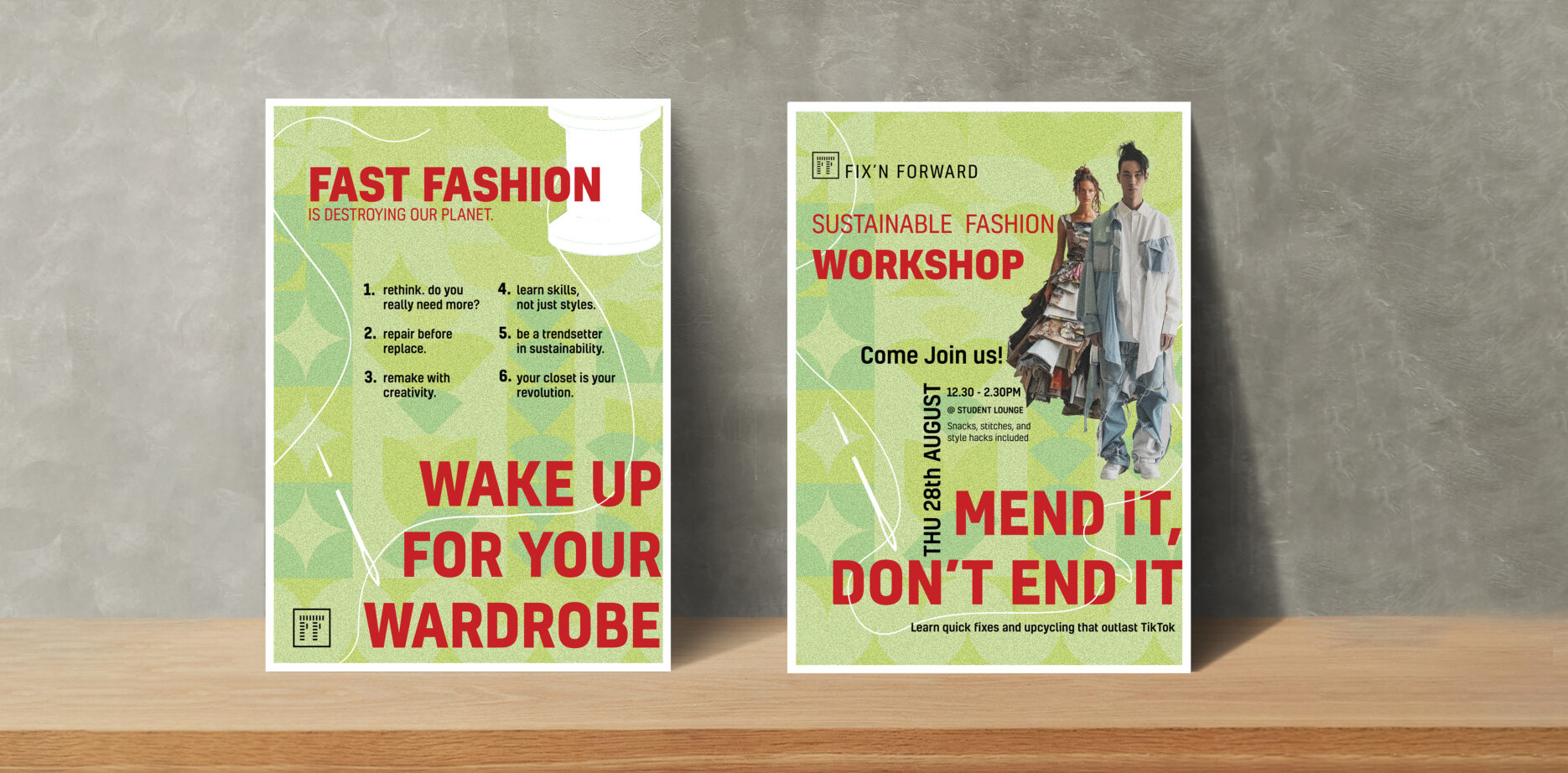

The primary goal of this practice-based user experience project is to promote garment repair and upcycling as everyday solutions among communities in New Zealand, addressing the environmental and social implications of fast fashion. This project explores upcycling, refashioning, and repair culture as pathways toward a sustainable circular fashion economy. By positioning discarded garments as valuable resources, the work challenges perceptions of second-hand clothing and highlights repair as both a practical skill and a cultural practice. By developing prototypes through deconstruction and reconstruction processes, as well as through the experimental making of inventions called head-to-toe upcycling that utilize discarded garments and community-focused workshops, the project demonstrates how small acts of repair and upcycling can scale into broader cultural shifts, reframing fashion as a cycle of care, creativity, and resilience rather than overproduction and waste.

INTRODUCTION

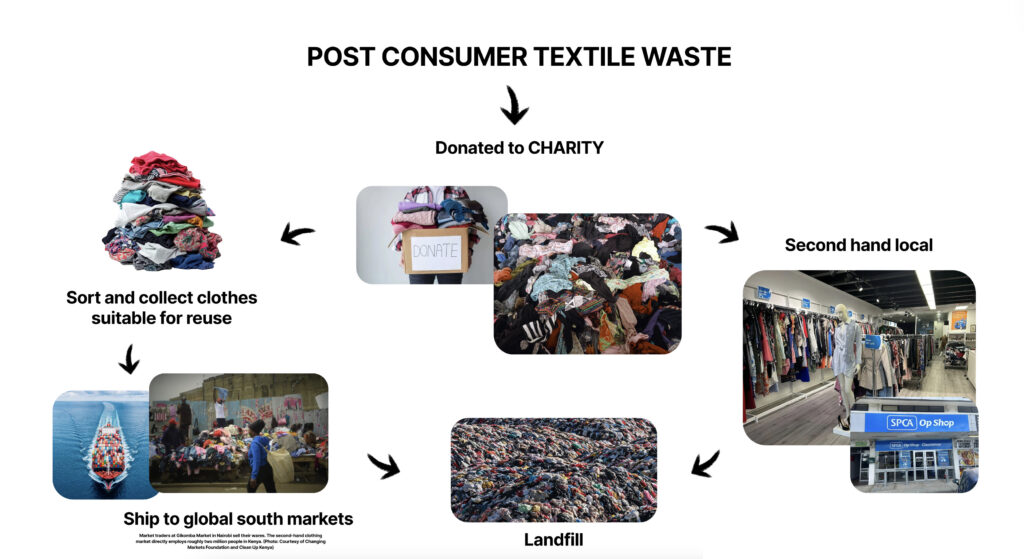

The fast fashion industry drives unsustainability through its rapid production of low-quality, cheap clothing that replicates current fashion trends. Large retailers manufacture billions of garments and distribute them worldwide with minimal delay, ensuring the latest designs reach consumers within hours of the runway shows. The modern “ throwaway” culture and this system

fuel overconsumption and generate mountains of textile waste; much of it ends up in landfills or incinerators or is exported to developing countries. Although there is a growing awareness of these issues, many students and everyday consumers are uncertain about whether their individual choices can make a difference.

In contrast, small clusters of consumers who are aware of environmental and ethical issues and interested in social change are turning to alternative models and niche inventions. These include students and community repair circles, upcycling community workshops, and small businesses that value discarded clothing as a resource rather than waste. These practices not only extend the lifecycle of garments but also encourage reflection on consumption, creativity, and care. Positioned within this context, this project explores how upcycling and repair culture can contribute to a sustainable, circular fashion economy—starting from the small scale of community action and growing into broader cultural change.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Fast fashion rose over recent decades, as did the increasing availability of cheap, low-quality clothing that is purchased and discarded at an accelerating rate. This shift has generated adverse environmental degradation and human exploitation (Fletcher, 2014). Fashion’s vast and opaque supply chains illustrate the excesses of Western consumerism, as ecological damage and social inequities can be traced across nearly every part of the production cycle, consumption, and disposal. The scale of these impacts has prompted growing recognition, even at institutional levels, of the urgent need to reform the fashion system (Fletcher, 2014). Extending the consumption period of the products is one effective approach to minimize the impact (Islam et al., 2020; McLaren et al., 2016; Rotimi et al., 2021). Extending the lifespan of garments by just three months can reduce their waste footprint by up to 10% (Cooper et al., 2013; McLaren & McLauchlan, 2015; Stanescu, 2021).

However, the fashion industry is mismatched with the idea of preserving clothing for a longer period of time, as it lives on novelty and is structured for deliberate product obsolescence (McLaren et al., 2016). Furthermore, a lack of skills in mending and reusing clothes has become a barrier to extending their duration (Lapolla and Sanders, 2015; McQueen et al., 2023; Zhang and Hale, 2022), and consumers do not assume responsibility for extending product lifespan (Cox et al., 2013; Mishra et al.,2020).

Shifting consumers away from fast fashion remains challenging, even among the more ethically minded (Fletcher, 2014). Individuals have different decision-making practices and differential responses to social norms. Even the most ethically minded engage in ‘grey’ consumption and are susceptible to planned obsolescence of fashion cycles (McDonald et al., 2012). Despite growing environmental awareness, a value–action gap persists in clothing consumption, as consumers continue to prioritize low-cost, trend-driven fashion over sustainable alternatives (Henninger et al., 2016; Cho et al., 2015; Joy, 2012). Clothing also functions as a visible expression of social identity, which means that fast fashion is sustained not only by affordability but by its cultural significance (Blazquez et al., 2020). This dual pressure—economic and social—helps explain why many consumers, even those who claim environmental concern, still engage with fast fashion. Addressing the gap, therefore, requires more than providing sustainable options; it calls for strategies that reframe identity and status away from disposability and towards practices such as repair, customization, and shared ownership.

In Almanac for the Anthropocene, DIY practices such as mending, foraging, and community building are presented as imaginative strategies that resist consumerist culture while fostering resilience and sustainability (Wagner & Wieland, 2022).

Visible mending, for example, demonstrates how small-scale acts of repair can extend garment lifecycles, promote creativity, and encourage knowledge-sharing within communities. While these actions are not positioned as solutions to systemic

causes of the climate crisis, they are valued for cultivating alternative relationships with material culture and the living world. Complementing this, the book highlights a feminist care perspective, which calls for attention to how technologies and practices are imagined, produced, used, or repurposed in “care-full” ways (Wagner & Wieland, 2022).

Drawing on Tronto’s framework of care and Puig de la Bellacasa’s notion of interdependence, this approach situates solarpunk as a practice of responsibility and connection across human and more-than-human entanglements. Together, these perspectives frame DIY and care as interlinked modes of reimagining social and ecological futures through everyday practices.

Refashioning positions consumers as active participants in the design and production of clothing, rather than passive end-users. Fletcher (2008) conceptualizes this as the role of the “user as maker,” where individuals engage directly in creative and practical aspects of clothing. This process not only fosters personal skills in garment construction but also enhances feelings of self-expression and satisfaction, whether creating for oneself or for others (Hirscher, 2013).

Researchers discovered that even though the skills needed to repair clothing have declined, consumers still want to fix expensive or valuable clothing, particularly since paying for such services is seen as prohibitively expensive (Fisher et al., 2008).

Researchers from Norway discovered that if consumers were better at fixing their clothing, they would wear it for longer. The simplest operations, including sewing on a button (73%), repairing an unraveling seam (55%), patching clothing (31%), darning clothing (27%), and adjusting pant length (26%) were most likely to be performed by at least half of the respondents in a 2010 poll who said they occasionally repair clothing. If they were better at it, one respondent said, they would be more inclined to fix their clothes. Some high-income families would perform repairs if they had the time and capacity, but low-income families were more inclined to do so (Laitala & Boks, 2012). None of these studies, however, evaluated consumers’ real capacity to sew, mend, or carry out other clothes care tasks (Norum, 2013). In the context of my project, this participatory approach could be positioned as a tool not only for skill-building but also for shifting collective attitudes toward repair culture.

NEW ZEALAND CONTEXT

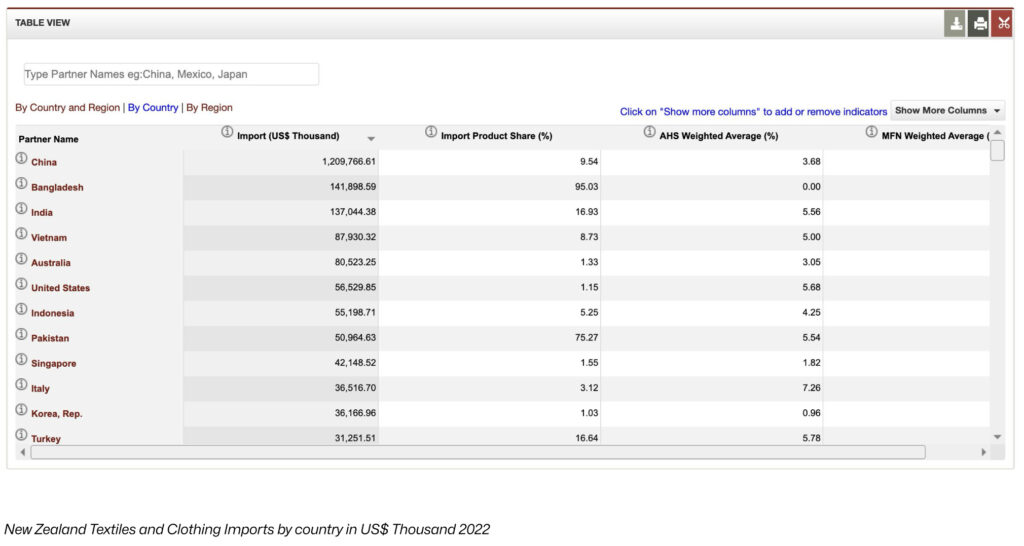

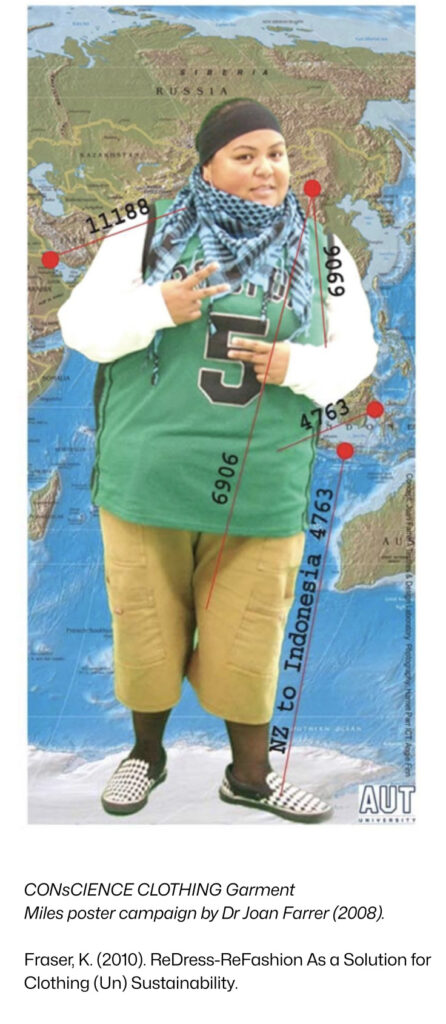

New Zealand, which once thrived in the domestic apparel industry, has significantly diminished and can no longer supply the required appropriate raw materials to the apparel industry.

Most of the materials must be imported to manufacture clothing products in New Zealand, and mainly from China. This means New Zealand fashion products carry a substantial carbon footprint at the start of the fashion supply chain, attributed to garment miles.

Textiles accounted for 5% of landfill waste in New Zealand in 2019, with projections indicating a potential rise to 14% by 2040. Every year, around 220,000 tonnes of clothing and textile waste is thrown away in New Zealand landfills. The average New Zealander throws away at least 13 kg of clothing and textiles each year.

https://wits.worldbank.org/CountryProfile/en/Country/NZL/Year/LTST/TradeFlow

PROBLEM STATEMENT

Fast fashion encourages overconsumption and rapid disposal, leading to massive textile waste in New Zealand. Repair and reuse practices remain undervalued and disconnected from mainstream culture. There is a need for design-led solutions that promote sustainable habits and community-based circular systems.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

- How might we build a connected ecosystem that supports ts circular fashion practices and empowers students to take action against textile waste?

- How can participatory design and community workshops help build local repair and upcycling networks?

- What creative systems—physical or digital—can support and scale a circular fashion movement?

HYPOTHESIS

Participatory workshops digital networks can inspire students to adopt repair and upcycling, creating a foundation for a circular fashion movement.

PRINCIPLES

- Participatory Design / Co-Design

- Service Design (CX + Touchpoint Mapping)

- Design for Behavior Change

GOALS

- Make sustainable fashion practices accessible through hands-on workshops.

- Teach youth practical skills in repair, upcycling, and customisation.

- Reduce reliance on fast fashion by encouraging everyday sustainable habits.

- Build peer learning and community around shared skills.

- Empower youth as advocates for sustainable fashion.

REFERENCE LIST

Beyer, H., & Holtzblatt, K. (1999). Contextual design. interactions, 6(1), 32–42.

https://doi.org/10.1145/291224.291229

Bochner, A. P., & Ellis, C. (2016). Evocative autoethnography: Writing lives and telling stories. Routledge.

Cano, M., Henninger, C. E., Alexander, B., & Franquesa, C. (2019). Consumers’ knowledge and intentions towards sustainability: A Spanish fashion perspective. Fashion Practice, 12(1), 1–21.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17569370.2019.1669326

Charmaz, K. (2002). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

Cooper, A. (1999). The inmates are running the asylum: Why high-tech products drive us crazy and how to restore the sanity. Sams Publishing.

Cooper, T., McLauchlan, S., & Morrissey, J. (2013). Managing sustainability in the fashion business: Exploring challenges in product development for clothing longevity. Nottingham Trent University.

https://irep.ntu.ac.uk/id/eprint/27463/1/PubSub4900_Cooper_NTUimprint.pdf

Cox, J., Griffith, S., Giorgi, S., & King, G. (2013). Consumer understanding of product lifetimes. Resources, Conservation & Recycling, 79, 21–29.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2013.05.003

Curedale, R. (2013). Service design: 250 essential methods. Design Community College Inc.

Denzin, N. K., & Giardina, M. D. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and the conservative challenge. Left Coast Press.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2011). The Sage handbook of qualitative research (4th ed.). Sage.

Fisher, T., Cooper, T., Woodward, S., Hiller, A., & Goworek, H. (2008). Public understanding of sustainable clothing: A report to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). Defra.

Fletcher, K. (2008). Sustainable fashion and textiles: Design journeys. Earthscan.

Fletcher, K. (2014). Sustainable fashion and textiles: Design journeys (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Fraser, K. (2010). ReDress–ReFashion as a solution for clothing (un)sustainability [Unpublished manuscript].

Gwilt, A. (2014). Fashion design for living: Upcycling, sustainability, and the circular economy. Bloomsbury Academic.

Hanington, B., & Martin, B. (2012). Universal methods of design: 100 ways to research complex problems, develop innovative ideas, and design effective solutions. Rockport.

Henninger, C. E., Alevizou, P. J., & Oates, C. J. (2016). What is sustainable fashion? Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 20(4), 400–416.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-07-2015-0052

Hirscher, A. L. (2013). Joyful sustainability: A new concept for sustainable fashion design. In L. F. M. Cooper, H. Bremner, & J. Hill (Eds.), Fashion: Connecting theory to practice (pp. 143–154). Inter-Disciplinary Press.

Islam, M. M., Perry, P., & Gill, S. (2020). Mapping environmentally sustainable practices in textiles, apparel and fashion industries: A systematic literature review. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, 25(2), 331–353.

https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-07-2020-0130

Jacobs, K., Petersen, L., Hörisch, J., & Battenfeld, D. (2018). Green thinking but thoughtless buying? Journal of Cleaner Production, 203, 1155–1169.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.08.270

Joy, A., Sherry, J. F., Venkatesh, A., Wang, J., & Chan, R. (2012). Fast fashion, sustainability, and the ethical appeal of luxury brands. Fashion Theory, 16(3), 273–296.

https://doi.org/10.2752/175174112X13340749707123

Kalbach, J. (2016). Mapping experiences: A complete guide to customer alignment through journeys, blueprints, and diagrams. O’Reilly Media.

Koch, K. M. (2021). Clothing upcycling in Otago (Ōtākou) and the problem of fast fashion (Master’s thesis). University of Otago.

https://hdl.handle.net/10523/10670

Dan, M. C., Ciorțea, A., & Mayer, S. (2023). The refashion circular design strategy – changing the way we design and manufacture clothes. Design Studies, 88, 101205.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.destud.2023.101205

Laitala, K., & Boks, C. (2012). Sustainable clothing design: Use matters. Journal of Design Research, 10(1–2), 121–139.

https://doi.org/10.1504/JDR.2012.046142

Lapolla, K., & Sanders, E.-B.-N. (2015). Using co-creation to engage everyday creativity in reusing and repairing apparel. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 33(3), 211–226.

McDonald, S., Oates, C. J., Alevizou, P. J., Young, C. W., & Hwang, K. (2012). Individual strategies for sustainable consumption. Journal of Marketing Management, 28(3–4), 445–468.

McLaren, A., & McLauchlan, S. (2015). Crafting sustainable repairs: Practice-based approaches to extending the life of clothes. In Product Lifetimes and the Environment (PLATE) Conference Proceedings (pp. 221–228). Nottingham Trent University.

https://www.research.ed.ac.uk/files/172718271/McLauchlan2015CraftingPLATEConf.pdf

McQueen, R. H., McNeill, L. S., Kozlowski, A., & Jain, A. (2022). Frugality, style longevity and garment repair. International Journal of Fashion Design, Technology and Education, 15(3), 371–384.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17543266.2022.2076361

Norum, P. S. (2013). Examination of apparel maintenance skills and practices. Family & Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 42(2), 124–137.

https://doi.org/10.1111/fcsr.12047

Patton, J. (2014). User story mapping: Discover the whole story, build the right product. O’Reilly Media.

Pruitt, J., & Adlin, T. (2010). The persona lifecycle: Keeping people in mind throughout product design. Morgan Kaufmann.

Rotimi, E. O. O., Topple, C., & Hopkins, J. (2021). Sustainable practices of post-consumer textile waste. Sustainability, 13(5), 2965.

https://doi.org/10.3390/su13052965

Stanescu, M. D. (2021). Post-consumer textile waste upcycling to reach zero waste. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28(12), 14253–14270.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-12896-2

Stickdorn, M., Hormess, M., Lawrence, A., & Schneider, M. (2018). This is service design doing: Applying service design thinking in the real world. O’Reilly Media.

Wagner, P., & Wieland, B. C. (2022). Almanac for the Anthropocene: A compendium of solarpunk futures. West Virginia University Press.

West, J., Saunders, C., & Willet, J. (2021). A bottom-up approach to slowing fashion. Journal of Cleaner Production, 296, 126387.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126387

Zhang, L., & Hale, J. (2022). Extending the lifetime of clothing through repair and repurpose. Sustainability, 14(17), 10821.

Leave a Reply